As told to Linda Jacobson (lindaj@well.com)

LJ: Paul, what were you doing in 1984 — the year before you became a founding staff member of Opcode Systems? How would you describe the “work lifestyle,” routine, and group dynamic behind-the-scenes in your world then? Was the SF Bay Area audio industry back then influenced more by the cultures of the computer industry and Silicon Valley, music industry, San Francisco scene, and/or film industry and Hollywood?

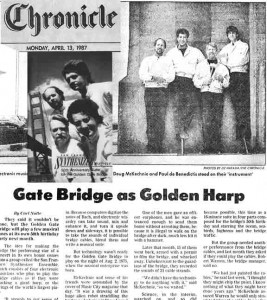

PdB: In 1982 I had purchased a Rhodes Chroma synth and in 1983 created one of the first computer-based electronic music “home” studios in the San Francisco Bay Area around that instrument. I had added the Apple II computer and the sequencing and editing software from Fender along with the SIMPLE System synchronizer for video and audio and the requisite mixers, mics, speakers, 2-channel and multitrack tape decks. I was composing music for film and television and through my friend Doug McKechnie’s connection at Lucas Film I even had a chance to write a demo cue for the final Ewok scene in the latest Star Wars: Return of the Jedi movie, apparently Lucas wanted to hear some other ideas than what John Williams had come up with. Three of us in the San Francisco Synthesizer Ensemble got to write a sketch for the cue. It was exciting to see part of the movie before it came out.

The Rhodes Chroma and Chroma Polaris

People were coming to me with their original music as well and I was helping them realize it on synths with the sequencer. They wanted more control and more editing. One project was the complete score to a Traveling Jewish Theater piece that was brilliant. I still had a day job and was trying to make a dent in the local film and TV scoring scene.

My Emu Drumulator had a JL Cooper mod for 3 optional chip sets which I got from Peter Gotcher and Evan Brooks at DigiDrums —later to become Digidesign. I became friends with them both and used to call Peter at Dolby where he had his day job. Evan used to program custom snare chips for me. It was a very small industry at that point.

Emu Drumulater with JL Cooper 3-Kit set, using “DigiDrums” chips from Evan Brooks and Peter Gotcher, who later formed Digidesign

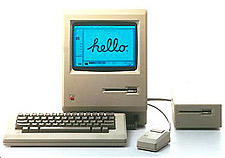

When I first saw the Macintosh computer at Macy’s in San Francisco they demoed “MacPaint” and I immediately tried to find the “music software” for it, but there wasn’t anything available. A local Macintosh specialty shop called “Mac Studio” – nothing to do with music though- hired me to find the music software for Mac after I showed the manager my computer music studio with the Chroma and Apple II.

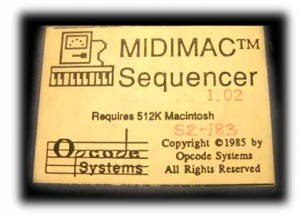

One day Ray Spears, who wrote the first “MIDI Mac Sequencer” manual for Opcode, came into the store to print the beta manual. I just happened to be in the store that afternoon and I was reading the pages coming off the LaserWriter printer and noticed the word “MIDI” and I introduced myself to Ray and he introduced me to Dave Oppenheim, and I immediately got involved in Opcode. This was before the products were shown publicly at the Summer NAMM show in New Orleans in 1984. I began helping with tech support, sales and product evangelism, then traveling to Palo Alto to Dave Oppenheim’s house where the company began. I ended up writing the manual for MIDI Mac Sequencer version 2.0 along with Dave.

Upon meeting Dave the first time I took him to my music studio and showed him how my “FSK” sync worked between my Emu Drumulator and the SIMPLE System, with SMPTE on the tape, video, etc. And I told him there must be something like this for MIDI. He got the MIDI spec and we borrowed a drum machine from Haight Ashbury Music, (the new owner Masoud and I went to music school in Marin in the 70’s), and Dave and I sat together all day working on MIDI Sync for their “MIDI Mac” sequencer. Finally Dave made the Opcode Mac sequencer and drum machine sync together. It was a thrilling moment for me, I hadn’t had that experience before. I think that day was the beginning of me giving up my day job and starting to work at Opcode and in the computer music industry.

My involvement with Opcode began very casually, Gary Briber was Dave’s partner in Opcode and had talked Dave into selling the software and MIDI interface he had engineered — he was going to give the software away! It was just the two of them when I started working at Opcode, I was the first employee.

We used to sit around Dave’s house at the kitchen table hand assembling MIDI interfaces, trying not to get leftover peanut butter sandwiches on the nice aluminum cases and copying 400K floppy disks one at a time, then hand writing serial numbers on them in red pen.

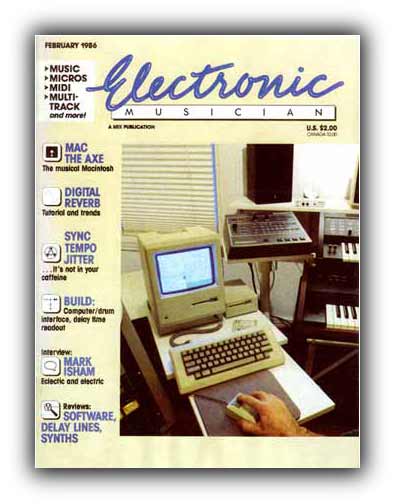

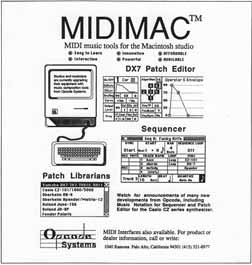

Late one afternoon Electronic Musician Magazine called up and asked if we had any pictures of the Macintosh in a music studio for their next issue. I said “Sure, I have some photos” then I went home that night and shot the color slides of my studio with the Mac using my Nikon and a tripod and timer, which became the cover of EM that month. I wanted some “human element” in the photo so I put my hand on the Macintosh mouse. (Below: The EM cover from February 1986, and the Opcode ad from that issue – click to see a larger version of them. The “Mac the Ax” article mentioned on the front cover was by Peter Gotcher, soon to be founder of Digidesign)

Dave Oppenheim also created a Macintosh “patch librarian” software application early on. I had gotten a MIDI adaptor for the Chroma at that point. I brought the spec for my Chroma to Dave’s house one day, he looked it over, wrote the software, and I went home that day with a patch librarian for the Chroma. I remember it worked fine, I’m not sure if he ever changed any code in the Chroma librarian in Opcode’s 15 year history. We were all just doing what we could as fast as we could in real time. There was a feeling of so much to try out, very little boundaries and with Dave as both a musician and electrical and software engineer sometimes things just happened as if by magic. One day there wasn’t a feature or even a product, the next day there was.

I was also performing in the San Francisco Synthesizer Ensemble (SFSE) in the early 1980’s. Along with playing my synth parts, I was in charge of running the live Mac sequencing that we all played along with. I was using some of the performance features to trigger sequences live and some of the randomization “generated sequences” to make every performance a bit different. It worked most of the time, amazingly. At one point we sampled the cables of the Golden Gate Bridge and “played” them on our keyboards, and recorded a special “Suite for the 50th Anniversary of the Golden Gate Bridge.” It got quite a lot of press coverage after a reporter asked “How did you get to record the bridge?” Doug McKecknie, the founder of the SFSE (who had conceived the idea of “playing the bridge” in the late 60’s), told him that at first the Golden Gate Bridge district wouldn’t let us record because we needed to hit the cables with a rubber hammer. So he said we wouldn’t. Then we did anyway. McKechnie told the reporter: “We lied in the interest of science.” That quote got written up everywhere. We ended up on Entertainment Tonight, The Evening News with Tom Brokow, local TV and CNN. People today still mention it. One musician I met remembers seeing the news about it in Germany on CNN.

LJ: In what ways have the computer industry and Silicon Valley influenced the audio industry?

PdB: From my direct personal esperience, I think Dave Oppenheim’s combined music skills and knowledge with his Stanford engineering education became fertile ground for experimentation. At first, like Dave, I think many innovators in the music industry wanted to make something for themselves to use, then it became a product. It seems like many of the early computer music companies had this kind of start.

I’m not sure of how the film industry played into it in those early days, I know George Lucas was trying to put computer systems together to streamline audio and video production. Today everything in audio for film and TV is digital and it’s all very integrated, thanks to standards such as Apple’s QuickTime and other high-end compression and digital video standards and powerful, relatively affordable computers.

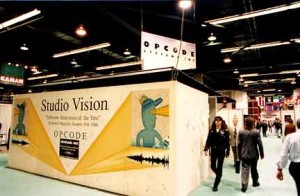

Looking back at 20 years in the computer music industry I think one of the biggest contributions and most important connections for me is being a musician and composer and working with engineers to help guide products. In the late 1980’s I was carpooling to work with Mark Jeffery who was an engineer on Digidesign’s Sound Tools at the time, and a musician himself, we were both using Opcode’s Vision MIDI sequencer and talked about how nice it would be to have Sound Tools and Vision combined so that we could put guitar and vocal tracking into the sequencer without syncing to tape. I went to work that day and suggested the idea and the idea for Studio Vision, the first Audio and MIDI sequencer, was born. (Note: I have been trying to find the staff meeting notes from that moment in time but have yet to get corroboration on this event, Mark Jeffery seems to remember our conversation, and Dave Oppenheim recently told me ‘that could be right, it was a long time ago I don’t remember’ — but that’s the way I remember it! -pdb) Originally upon introduction Studio Vision was called “Audio Vision” – this was before Digidesign was purchased by AVID – and for whatever reason we did not search the name well enough. After the NAMM show introduction in 1990 we brainstormed on new names for it. I had named the “Studio 3” MIDI interface and suggested we carry on the “Studio” moniker into our software line, so it became Studio Vision and we re-launched it.

Because no one had introduced a product in our music software markets with this idea of combining audio and MIDI on a computer, we were able to keep Studio Vision a secret throughout its initial alpha testing and up until the 1990 NAMM show. So I had this idea to get an artist reaction of seeing Studio Vision the first time and recording that moment on video and using it at the upcoming NAMM show to premiere the software. Thomas Dolby had become a big fan and deep user of Opcode’s Vision so I called him up and asked if I could fly in to LA with a video camera crew and show him something no one had seen before that Opcode had invented. He agreed, and I did just that. He immediately grasped how cool it was, and instead of just a reaction video, he asked me to go out to lunch, he’d record a song with it, and plan to re-record it live in front of the video camera. Which he did. It was amazing. Instantly showing the power of recording audio and MIDI in the same application. He recorded some MIDI drums, MIDI bass, and MIDI keyboards, then picked up a microphone, chose a new track, donned some headphones and recorded the vocals. We used the video at NAMM, and Thomas even stopped by the booth. He later recorded one of my favorite albums “Astronauts and Heritics” using Studio Vision.

A disk label from the very first commercially released Macintosh ‘sequencer’ from Opcode, Apple later made the company change the name of the product, it eventually became “Vision” then “Studio Vision”

There’s no doubt that innovations in computer technology spurred innovation in the music industry. From the day the Rhodes Chroma came out computer control and memory inside a musical instrument became a given. Obviously the DX 7 was the big hit of the era and had MIDI but the concept was the same: a computer in a box running sound generating algorithms with a music keyboard attached to it. As computer companies such as Apple added new ports and card slots to their computers and offered software engineering tools that audio and music developers could use to create products, the industry moved forward. The Mac with two modem and printer serial ports allowed Opcode to make the Studio 3 MIDI interface, we almost built a modem right into it, but it cost a little too much at the time. When Apple added color, Dave Oppenheim added color to Vision and made a new standard of viewing data in color for quicker recognition of the music on the screen in non-notation graphic editing views.

At one point we realized that our customers’ MIDI systems we getting bigger and bigger, partly due to rackmount synths where people had huge racks, and there was a limitation on how many MIDI channels you could access at once. The solution was a kludge at best using ‘MIDI Patchers’ — like audio patchbays but for MIDI — that responded to program changes so that the next track that was playing on your sequencer would play the right sound on the right instrument, on the right patch. Apple had “MIDI Manager” and since we only offered solutions for Mac users that was what we tried to use. But its development was too slow for the market and our needs. That’s when Doug Wyatt and Dave Oppenheim came up with the concept of OMS — originally called the ‘Opcode MIDI System’ but quickly changed to the ‘Open MIDI System’ so that other software and hardware developers could use it. We ended up hiring Mark Lentzner from Apple who had worked on MIDI Manager. And we had the Studio 5, a 15-port, 240 MIDI-Channel, interface in development and needed way-more MIDI Channels than Apple offered in MIDI Manager.

We had planned to also have six Studio 5 interfaces able to be networked together for a massive 1440 channel access, instantly without any MIDI switcher. The studio 5 became the flagship interface, then we put out the Studio 4 at a more modest price. Jeff Bova had an amazing multi-rack system I believe using six Studio 5s at his synth room at The Hit Factory in New York. The other thing that OMS offered with the Studio 5 and then partially in the Studio 4, was a patching system that allowed extremely sophisticated routing and MIDI program change and Mapping of MIDID Messages. I believe its still unrivaled today, as on the 2006 Pat Metheny Group tour expert technician Bob Rice set up keyboardist Lyle Mays system with a Studio 5, OMS+Patches running on an ancient Laptop so that he could do the show live. It’s still the best choice apparently for Lyle to be able to send the patch changes, MIDI messages and control whatever keyboards he needed to instantly. The album they were touring for was played as a single 68-minute piece, so they had no time to stop and set anything up! This is about 15 years after the Studio 5 was introduced.

Another moment that sticks in my mind was at a morning Opcode staff meeting where Dave Oppenheim told us how he had an idea that would help customers share songs and MIDI tracks between different sequencers like Mark of the Unicorn Performer and Vision. He said there was a MIDI Manufacturers Association meeting at the Chicago Summer NAMM show where he was going to suggest a new file format called a “MIDI File” — everybody voted for it at the meeting I guess. It of course became the “Standard MIDI File” format. Dave was like that, he’d hear about a problem, and come up with an immediate solution. And in those early days it would be readily adopted. OMS was instantly adopted by almost every Mac developer, including Digidesign, except Mark of the Unicorn who had their own MIDI interface hardware and probably wanted complete control over their software and “system.”

LJ: In what ways has Silicon Valley influenced your work in the audio industry, with respect to culture and business operations?

PdB: Another innovator in the music industry, Scott Silfvast the founder of Euphonix, is a musician and engineer as well. He told me that when he was mixing some of his music he wanted to have recall of everything, but none of the studios or consoles would do that. So he built his own and created the Euphonix console. He also came up with the idea for delivering audio mixes over the Internet in 1999. I spent over a year at Euphonix exploring this with Scott and Rocket Network. We created a simple software application designed just for this purpose: eDeck. Now Digidesign has adopted the Rocket Network technology and I think we’ll see this become a reality of day-to-day business in the near 5-10 year future. Security is still an issue, but it may be solved. Stand in the lobby of a busy LA recording studio and watch the fed-x packages with rough mixes fly out the door. Those packages might disappear someday, replaced by digital online transfers.

I also headed up the Euphonix marketing communications department for another year and became quite familiar with digital console technology as well. This is another area that Silicon Valley has influenced tremendously. A Euphonix console is essentially a network, with several computers and Ethernet, Firewire cables and other software and hardware standards connected together to serve the audio professional. Euphonix has been smart to use the billion-dollar R&D of networking companies to help create standards that they can use to build a professional audio product. Their ‘networked audio’ console format will undoubtedly become the standard in the future.

Euphonix was full of musicians who were also engineers, with the right product management guidance they have brought out amazing technology for the audio industry. Once again, this special combination of computer software or hardware engineer with musicial talents has bred some unique products and I think has had a tremendous impact on the audio industry.

LJ: [Now think back to 1994. Big names on the pop charts: Sheryl Crow, Boys II Men, Gloria Estefan, Luthor Vandross and Mariah Carey. San Francisco is an international hotbed for geek chic and rave scenes. Phrases such as “virtual reality,” “smart drugs,” “cyberspace” are heard at San Francisco parties. Top movies: Forrest Gump, 4 Weddings and a Funeral, and Pulp Fiction. ILM earns an Oscar for FX for Jurassic Park, and Pixar wins its first patent for creating, manipulating and displaying images. Mainstream culture is hot for the 30-year-old Internet, thanks to the development of the “web” browser. Microsoft announces Windows 95 and a group of renegade programmers release Linux 1.0.]

Ten years ago — you had become a senior exec at Opcode. What was the work culture there in ’94? Regarding the audio industry in general back then, would you say it was most influenced by the cultures of the computer industry and Silicon Valley, music industry, San Francisco scene, and/or film industry and Hollywood? Elaborate if you will.

PdB: In 1994 Studio Vision was the most important application for composers with its combined audio and MIDI and musically friendly interface. It integrated smoothly–most of the time!—with Pro Tools which had become the standard digital audio hardware. We all continued to work very hard at being successful, because by that time there were several competing companies for Opcode including Steinberg, Emagic, Cakewalk and Mark of the Unicorn. The market got small real quickly in the mid to late 1990’s. Being in Silicon Valley we always thought we had a technological advantage but I’m not sure looking back now. If you could secure a large base of users with a sequencer that they were dedicated to and then support them with other products while maintaining the sequencer you had a reasonable business. It became all about dealer sales relationships, shipping new versions, and the “next big thing.” If you didn’t have the next big thing, someone else did. Then the Internet took off and everything morphed in Silicon Valley.

I remember working with Flood and Trent Reznor one day in LA at the house he rented and set up his studio in and watching Trent just record long jams into Studio Vision. Then he and Flood would piece together interesting parts. It all worked so fast compared to earlier ways of recording and editing. And you could totally relax and try stuff without the pressure of the studio clock. At one point Trent even said “I can’t even write a song without Studio Vision.” Which is of course ridiculous, he’s a monster musician and could do anything he likes, but the technology created a new mindset. NIN’s “The Downward Spiral” was pretty amazing stuff.

The Dust Brothers, John King and Michael Simpson, were big fans of Studio Vision and the way you could cut and paste and create a musical collage. They really pioneered that sound before there was a visual way to do it. Once they could see the music and grab phrases and move them around in Studio Vision it became their standard musical palette. Beck’s “Odelay” had a lot of Studio Vision collage happening, it sounded great. It’s a standard way to work today, but it was revolutionary back then.

Film composers also latched onto the power of computers and Vision became their main tool, giants like Thomas Newman and James Newton Howard. Today [in 2004] I believe a few folks are still using Vision to compose because of some of the unique ways you can work with music and musical phrases. I believe Thomas Newman and Mark Mothersbauogh only recently —[in 2007]— stopped using Vision. The computer and digital technology really gave composers their “palette” that painters have had for a thousand years. It has created a new era in composing.

LJ: I’m wondering whether you think the computer industry’s work culture (not tech advances) helped or hurt the audio industry

PdB: The 7-day-work-as-many-hours-as-possible work week was definitely a part of Opcode’s culture. I know I worked all the time, and I believe several of the key engineers did as well. But at the time the rewards seemed worth it. Opcode was one of the premiere companies in the world, doing what we did, innovating in music and computers, creating standards like the MIDI File, OMS, the universal librarian, integrating audio and MIDI recording and editing with Studio Vision. Some of the best music of the day, from Cyndi Lauper, Seal, U2, Paul McCartney, Beck, Branford Marsalis, Chick Corea, KC Porter, Thomas Dolby and Nine Inch Nails to the Smashing Pumpkins, The Rolling Stones, Jerry Harrison, Brian Eno, Herbie Hancock, Jeff Lorber, Prince, 311, INXS, Steve Vai, Carlos Santana and even Steely Dan— was being created using our products.

Bryan Bell of SynthBank introduced me to al lot of major artists in those days, including Herbie and Branford, and as I met people they would introduce me to others and I would introduce them to Opcode products. That was a reward for me, meeting many of my living heros, and becoming friends with some of them. Bryan sold so many Opcode Patch Librarians for artist studio systems we finally just made a special disk of all the librarians together for him to sell, this eventually became Opcode’s “Universal Librarian” and was available to all customers.

There was an unstated mantra that ‘the more hours you work the better’ at Opcode. Most of us followed it. I believe the computer industry’s work culture was transferred to the new ‘high-tech computer music’ industry. One common belief is that if you drive around and look into company parking lots in Silicon Valley on a Sunday, the one with the most cars in it and lights on, and activity in the building, is the one to invest in. It’s a mindset.

I know Dave Oppenheim had worked at pioneer Nolan Bushnell’s Androbot and other Silicon Valley firms before starting Opcode. I think ultimately working long hours helped the fledgling computer music industry form faster than it would have. Innovations emerged faster. But in a way it all seems a bit inevitable, in hindsight, because the main people working, at least in engineering, were from the tech industry already. So they’d probably work in the same way whatever product they created.

LJ: What do you mean by “with the right product management guidance”?

PdB: As important as the engineers are who make the magic come alive as a usable product (and they are artists themselves in my opinion), product managers who are accomplished musicians, understand the process of making music and interact with musicians of all types—from performing and recording to composing—they help complete the circle of creation for these music products. There needs to be a musical influence in high tech music product creation or you end up with technologically powerful, feature-rich products that don’t fit into the music making process, or are actually kind of hard to use and non-musically intuative. They are mostly just hard to use. I think we accomplished creating very musically useful products at Opcode, and I think Scott Silvfast at Euphonix did the same thing. It was a partnering in hard work and doing the right work, from planning to execution.

Odelay by Beck: The Dust Brothers, John King and Michael Simpson, were big fans of Studio Vision…Beck’s “Odelay” had a lot of Studio Vision collage happening, it sounded great. It’s a standard way to work today, but it was revolutionary back then.

As a product manager, I helped create a piece of software [“eDeck”] at Euphonix that was functional and easy to use, hid the technology, yet allowed everyday users to get their job done more easily, more elegantly. The engineers worked hard to create it. Scott Silfvast and I worked hard to make sure it was the right set of features with the right user interface and user experience. As far as Euphonix consoles go, as Communications Director I helped get the word out to the world what a great product they have. I told some success stories. I wasn’t involved in product management and engineering at Euphonix at that point, but I was surrounded by very intelligent, inspired engineers and product managers —many of them musicians. The combination of the two is what seems to create the great products in our audio industry.

LJ: Were the Euphonix engineers and programmers working 12-15 hour days? Did Management provide free caffeine and chocolate snacks? Did people sleep under their desks? You describe a group of computer engineers with musical talents– so were they taskmasters obsessed with churning out elegant code and efficient motherboard designs or were they creative, project-oriented guys who were more interested in outcome than process?

PdB: I do remember people working insane hours at both Opcode and Euphonix. 12-15 hours a day wasn’t unusual if I recall. Some people slept at the office when crunch time came. There were couches to sleep on at Opcode. It wasn’t something that happened all the time though. Mostly as a deadline became close, the release of a product or a special demonstration at a trade show or for the press. Everybody who had to get something done just did it. Personal time-off was a non-issue. But of course after a product release, there were definitely vacations. I finally took 3-weeks off one summer after working for about 10 years straight.

I’d say the engineers and product management worked very closely at Opcode and there wasn’t so much of a taskmaster attitude as a “lets all get this done” attitude. The product specs and launch plans were in many ways just as important as the code work. I always felt the code work was harder though, and much more magical. Software coding is really quite an art form, and underappreciated as art. The products almost live and breathe if done well. They are creations.

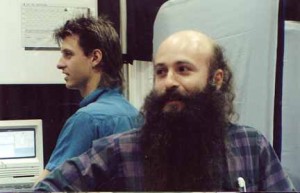

Opcode company photo circa 1990’s: Paul dB far left, Dave Oppenheim (center with beard), and Ray Spears (far right)

I think Opcode’s Studio Vision was in that category. I know many composers who swear there was just something about using it that was better than other software. Beyond features. It was well designed and cleverly written. Creating this kind of “product” was so much cooler than building a widget for the “tech industry,” I think it became worth it for people to work harder than anyone would imagine working to create it. At the same time, I know as a composer the process of creation is a big part of doing it and getting satisfaction. What composer really likes their last composition when they’ve stared the next one? I’m guessing engineers have a similar feeling. It’s the journey not the destination. And software gives a new twist in that you can update it constantly—a seemingly endless journey.

Management always tried to create support systems for people to work long hours, but I don’t think it was meant to coerce them into working harder. There was food in the fridge and drinks and snacks. There wasn’t a payoff. Coffee however was available, and if you’ve ever had Peet’s coffee it’s better than other brands, especially brewed strong. We all drank too much coffee! That will keep you working.

LJ: Did Apple Computer inform its serial-port-based developers and ISVs that the serial port was going away? Did this significant hardware alteration mean much longer working hours at Opcode, and for whom? How did Opcode employees react? Was there anger/frustration? Or was it a welcome change because it invited further innovation?

PdB: Guy Kawasaki was Apple’s original “evangelist” recruiting and supporting developers when I joined the industry in the early 80’s. He’s become one of my heroes, I have all his books, and I stay in touch with him to let him know what I’m doing and I watch what he’s focusing on too. He’s still an innovative thinker.

Dave Oppenheim and I worked directly with Guy Kawasaki in the early days, since the Opcode offices were always less than a half an hour away from Apple, we’d just make an appointment and drive down and see him. He’d give us the latest infor mation, we’d tell Guy what we were doing, then the information we needed would flow from Apple to our engineering and product marketing groups. Apple became more secretive as the years went on, because they couldn’t risk competitors gaining an advantage by knowing what they were going to come out with next.

mation, we’d tell Guy what we were doing, then the information we needed would flow from Apple to our engineering and product marketing groups. Apple became more secretive as the years went on, because they couldn’t risk competitors gaining an advantage by knowing what they were going to come out with next.

There were so many leaks about what was next in MacWeek magazine. I remember the serial port to USB and the Nu-Bus to PCI slot changes were a bit of a surprise. Those kinds of changes certainly made more work for folks, but you had to live with it. Back in the day Apple always made the best host for music —I know a lot of people don’t agree with that! but we thought so—and whatever they changed in their hardware or software, we just had to adapt to and continue to support our customers.

Working as the artist relations contact for Spectrasonics over the past 14 years has confirmed a lot of what I’ve learned over the past 20 years in the high tech audio industry. It’s the music that matters, it’s about creating products that support the musical flow.

Eric Persing, Spectrasonics’ founder and Creative Director, has created an environment at Spectrasonics that holds the act of music creation as the ultimate goal. He and his engineering team work tirelessly, way beyond normal hours, to make this happen. It’s a supportive and friendly atmosphere with lots of communication. Like Opcode it’s professional, it’s a business but contains an extended family-oriented feel to it. So the culture of Silicon Valley’s hard work and innovation continues in the music industry at Spectrasonics.

(Short excerpts of this interview appeared in Mix Magazines’ article “Silicon Audio — When The Computer Industry Met the Audio Industry” — November 2004) Opcode’s Studio Vision was entered into the TECnology Hall of Fame at the Audio Engineering Society (AES) conference in 2008. Visit TECnology Hall of Fame Notes from George Petersen